All in the family: U-M expert reflects on 5 decades focused on Nepal, from youth to leading 30-year study

When Bill Axinn's parents took him to Nepal in 1976 for their own work in agricultural and social development, he was "pretty upset to be missing seventh grade."

Axinn's parents brought him to the then-isolated Chitwan Valley, and he went from being sad to scared: On the plane with them was a goat, an animal he'd never seen in person.

"I didn't understand anything I was experiencing," said Axinn, whose many hats at the University of Michigan include serving as a professor of sociology and at the Institute for Social Research, as well as interim director of the Ford School of Public Policy's International Policy Center.

A two-year immersion in which he learned to speak Nepalese and had no contact with his Michigan home or other native English speakers beyond his parents put him, he said, "on a course I never changed."

Axinn's parents moved back to Nepal while he was in college and he visited every year. It was on these return trips he came to understand that no quick intervention, needs assessment or outcome study would adequately "tell the real story of the social impact of all the many things around us that change all the time."

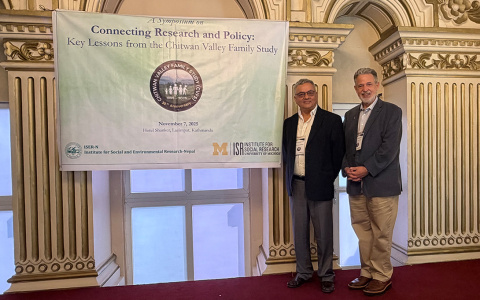

In that spirit and with the help of others, he launched the Chitwan Valley Family Study 30 years ago. It has accomplished many things but in the most basic terms it has worked to achieve one goal: "Study the same people, their families and neighborhoods for a long time."

On the eve of returning to Nepal to mark the study's milestone anniversary and continue to expand its work, Axinn shares his insights on current unrest in the country, key takeaways from his work and where it's going from here.

Recent unrest by young people in Nepal are part of a wave of Gen Z protests across the globe. What have you seen that might explain or foresee what has been happening?

There have been many important political changes across those 30 years. Our study maintains strict neutrality no matter what happens and continuously documents the changes in peoples' lives.

We do not measure political attitudes or behaviors, but we measure changes over time in local services sponsored by government and international donors. Clearly those services—schools, health care, transportation and others—have real, life-changing benefits for local people in Chitwan.

In Chitwan, as throughout Nepal, the spread and availability of internet access and social media allows citizens to be very aware of the government's priorities and how budgets and social programs are allocated. A cornerstone of our success in Nepal has been the exceptionally hard-working Nepalese people.

Both our data—30 years of documenting international migration patterns—and our experience building research capacity in Nepal are consistent with the trend of young adults increasingly deciding to leave to build their future. This trend plays an important role in the protests in Nepal, but perhaps also elsewhere.

Nepal occupies a crucial geopolitical location sandwiched between India and China. It's been described as a "buffer state" that must strategically balance interests. How might that dynamic play out in daily life and what changes have you noticed in the past few decades?

Nepal's population is a "melting pot" of people who moved there from nearby countries, especially India and China. This gives Nepalese families ties to their origins in both nations.

But Nepal has never been an easy place to live: rugged terrain, high altitude, wild predators, landslides, floods—and it is difficult to build everything. In this context, it has always been important for Nepalese to seek assistance from everyone who will give it: China, India, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, United States, Japan and others.

The assistance from all of these sources has built roads, bridges, hydroelectric plants, powerlines, agriculture, schools, health care and more. Our data show these changes help babies survive, people live longer, youth get more skills and adults get better jobs.

What stands out to you about life in Nepal and do some findings have broader implications beyond its borders?

Many societal changes came more recently and evolved more quickly than in other countries. This gave us the opportunity to document the independent consequences of specific changes, all of which have broader implications:

Education in schools is an independent source of change

Family life is a key motive for labor migration

Exposure to violence in the neighborhood has short- and long-term consequences to the people who live there

Social support groups can improve mental health independent of other circumstances

Where do you see your work going from here? Are there areas of study you'd like to expand into or other ways in which you expect the work to evolve?

By following neighborhoods of origin and all family members wherever they go—entirely independent of either opportunity or adversity—this study is uniquely able to document the long-term consequences of both opportunity and adversity. The work is evolving in three different directions:

Early-life predictors of aging and elderly health

Long-term neighborhood and family consequences for young child health

Consequences of the parental (and grandparent) generations for the life outcomes of young adults

Every year that goes by, not only does life continue but what we measure about life expands. I expect the value and use of these data to continue to grow.