More a spectrum than a switch: John Ciorciari talks shared sovereignty

John Ciorciari's office is neat as a pin, but a towering stack of books looms by his keyboard.

Ciorciari has just earned tenure. He's just been appointed director of the Ford School's International Policy Center. He's just returned from a week-long sojourn in China, where he accompanied Ford School students on their annual comparative policy exploration. And he's just won a spot on the Ford School's teaching honor roll—as he's done every semester he's taught.

But today, Ciorciari is poring through books, transcribing his latest interview notes, and thinking, quite seriously, about his next big project: a book about sovereignty.

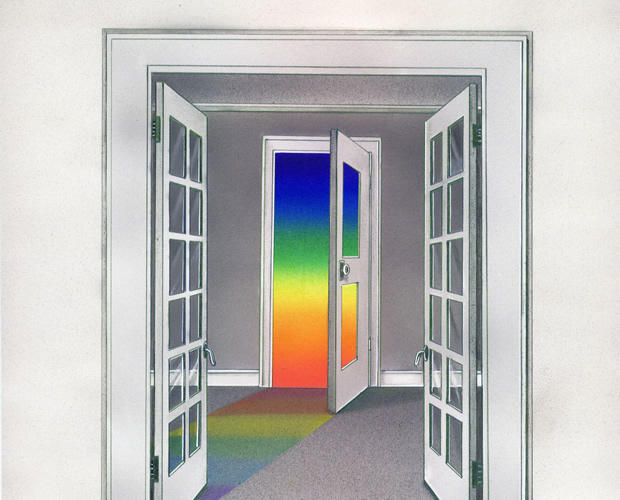

In an increasingly interconnected world—a world in which international trade, treaties, conventions, and collaborations have chipped away at traditional views of sovereignty—he says sovereignty, or the rights of nations to govern their affairs without outside interference, is more like a spectrum than a light switch.

At any given moment, countries might ask the question, "How much sovereignty am I exercising, and how much am I sharing with others?," says Ciorciari

At infrared, countries that need it might invite limited financial or technical assistance—like when a national police agency brings in foreign police advisors to train local counterparts.

At ultraviolet, countries or territories might host full-on international governance—like when the United Nations stepped in to govern Kosovo, until a new government could be established, in the wake of war.

Sovereignty-sharing, says Ciorciari, is somewhere in the middle of that spectrum. It allows countries to tap into the considerable functional capacities that international partners can provide, while strongly engaging local leaders in the process.

This kind of sovereignty-sharing can be particularly helpful to countries that are emerging from conflict. In these nations, ensuring basic security, a sense of justice, and peaceful transitions of power can be challenging, and the risk of falling back into conflict can be high.

"NO HOST COUNTRY WANTS TO ADMIT THAT IT'S SHARING SOVEREIGNTY, AND NO INTERNATIONAL ACTOR WANTS TO ACKNOWLEDGE THAT IT'S TAKING SOVEREIGNTY."

"Sovereignty-sharing is supposed to have the benefit of short-term assistance, but also long-term capacity building," says Ciorciari. "And it's supposed to be seen as legitimate both at home and abroad because both sides are deeply involved."

But sovereignty-sharing is difficult, and even the phrase is something of a dirty word in the international community.

"This term is almost never used in official dialogue because no host country wants to admit that it's sharing sovereignty, and no international actor wants to acknowledge that it's taking sovereignty," says Ciorciari.

For those who care not just about addressing conflicts and enforcing the peace, but also about building a climate for sustainable peace in all nations, that mutual denial is problematic.

If you don't talk about something, says Ciorciari, it's hard to improve it. And improving these arrangements—for host countries, and their citizens—is a worthwhile goal.

Somewhere, in his looming towers of books, and in his copious interview notes (Ciorciari expects to complete well over one hundred interviews with current and former diplomats, foreign service officers, and staff at think tanks, NGOs, and multilateral organizations before his work is done), Ciorciari hopes to find the recipe for successful sovereignty-sharing arrangements, particularly those that focus on key government functions like ensuring security, just courts, and fair elections.

If properly done, this type of sovereignty-sharing, he believes, can enfranchise host countries while also building a foundation for lasting peace.

John Ciorciari's research is made possible through support from an Andrew Carnegie Fellowship.

This story is from State & Hill, the magazine of the Ford School. View the entire fall 2016 State & Hill here.