Between a rock and a hard place: Mongolia’s fate within the international community

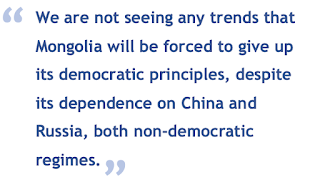

When we are faced with the question “Can Mongolia Survive?” our first reaction may be: Why wouldn’t it survive? Where would it go? Perhaps a better question we should be asking ourselves is – can Mongolia survive as a democracy? While Mongolia has been stable in its democratic development since the 1990s, its two largest neighbors – China and Russia – have considerable influence both in their relationship with Mongolia, and within the international community.

Historical Timeline:

1911: With the fall of the Qing dynasty, Mongolia proclaims independence from China. However, this does not lead to any real immediate independence, as Mongolia has no real military ability to defend itself and must first gain international recognition. As Mongolia looks for support, Russia takes the opportunity to insert its influence in Mongolia by assuring its autonomy from China.

1917 – 1921: For a brief period during the Bolshevik Revolution, China regains control of Mongolia until anti-communist and independent warlord Baron Ungern ousts Chinese forces from Mongolia. Subsequently, the Soviets chase Ungern out and become entrenched in Mongolia.

1921-1945: Mongolia is a de facto Soviet satellite state. It follows the USSR model of revolutionary transformation and socialism. In 1930, a Stalinist system is established which survives through the second World War.

1945: In 1945, a power vacuum occurs in China as the Guomindang and Chinese Communist Party (CCP) face the prospect of a civil war. Simultaneously, Stalin reaches an agreement with US President Roosevelt at the Yalta conference which assures effective US endorsement of Soviet claims in Mongolia. In the summer of 1945, Guomindang leader Chang Kai-Shek, angered that the US and the USSR were making decisions about China’s fate behind his back, sends one of his top advisers to Moscow for negotiations. As a result, he grants Mongolia de jure independence in return for Stalin’s support against Mao Zedong. Historical anti-Chinese sentiment amongst Mongolians makes independence an appealing prospect, and a referendum officially grants Mongolia independence in late 1945.

Late 1940s: Mao pushes to return Mongolia as part of China. Stalin plays key role in ensuring Mongolia’s political survival (importantly, this was out of Stalin’s interest to keep Mongolia as a buffer state between the USSR and China, not because of personal sentiments).

1980s: Parallel political openness and reforms occur in Mongolia as the USSR reforms under Gorbachev.

1990s: Serious democratic movement which leads to peaceful transfer of power.

Domestic Politics in the last 30 years:

Democratic Governance:

Mongolia has developed a strong presidency and parliament, with major parties which rotate in and out of power. Its democratic governance has seen situations where different parties control those two institutions, resulting in a power split between the presidency and the parliament. Remarkably, the transition of power between parties has been genuine and peaceful.

Two main parties:

Mongolian People’s Party (MPP): central-left party with stronger political force, and a more pragmatic economic policy

Democratic Party: coalition of several different factions; it is able to capture power on occasion in the parliament, and more consistently in the presidency

Characteristics:

The success of the democratic process in Mongolia may be slightly surprising, as Mongolia does not generally have rule of law. Two reasons why democratic rule may be preserved are considered to be the presence of open media outlets that participate in the political process, and the prevalence of a clientelist network. Nearly all families and groups have connections on both sides of the political spectrum, so the democratic process works through these connections.

Mongolia’s Foreign Policy: Russia and China

Russia:

As Russian interest in Mongolia after the fall of the Soviet Union subsided, Mongolia and its democratic process remained largely undisturbed. However, due to cultural attractions and resource dependency on Russia, Russia continued to exert considerable influence on Mongolia’s politics. While Mongolia does not wish to upset China, the political leanings of its leaders and cultural factors are moving Mongolia’s foreign policies in a direction which favors Russia.

China:

With China’s economic rise, Mongolia’s economic dependence on China has increased. Currently, more than 90% of Mongolia’s exports are to China, which gives China considerable leverage over Mongolia. Generally, it has been careful to exert such leverage, but some instances have occurred. For example, a Dalai Lama visit to Mongolia instigated Chinese economic threats, resulting in the Mongolian decision to apologize and promise it won’t happen again, despite strong religious ties to Buddhism within the nation.

Third Neighbor Policy

To balance the power of its two large neighbors, Mongolia has implemented a Third Neighbor Policy. This policy looks to the collective West for investment that can offset Mongolia’s dependence on Russian and Chinese capital. However this policy has recently been strained for various reasons:

1) Populist anti-West sentiment: Economic and resource nationalism makes it hard for Western mining companies to set up shop in Mongolia, and leads to reluctance from investors.

In light of these factors, it is likely that the Third Neighbor Policy will soon deteriorate. However, does this mean that Mongolia will increasingly be forced to move away from its democratic practices?